Galleys of the lagoon

Ecosystem-Based Management

**Apologizes, this page is under construction. For more information, please contact the author.**

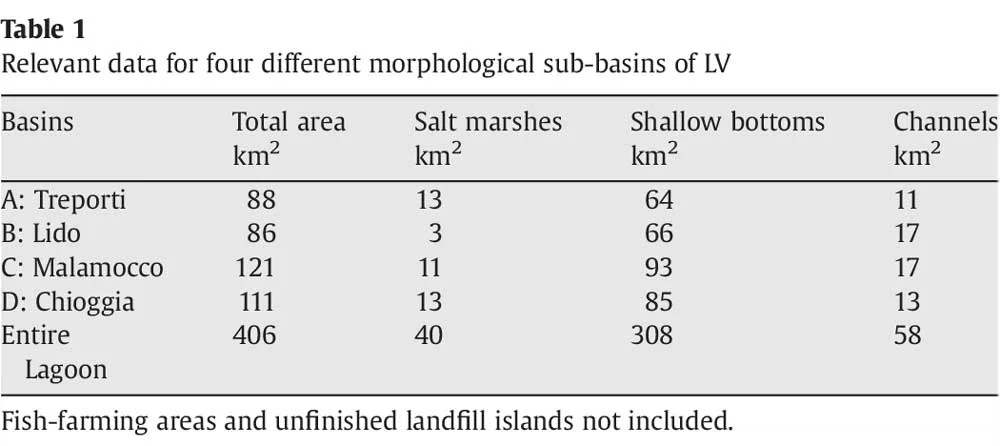

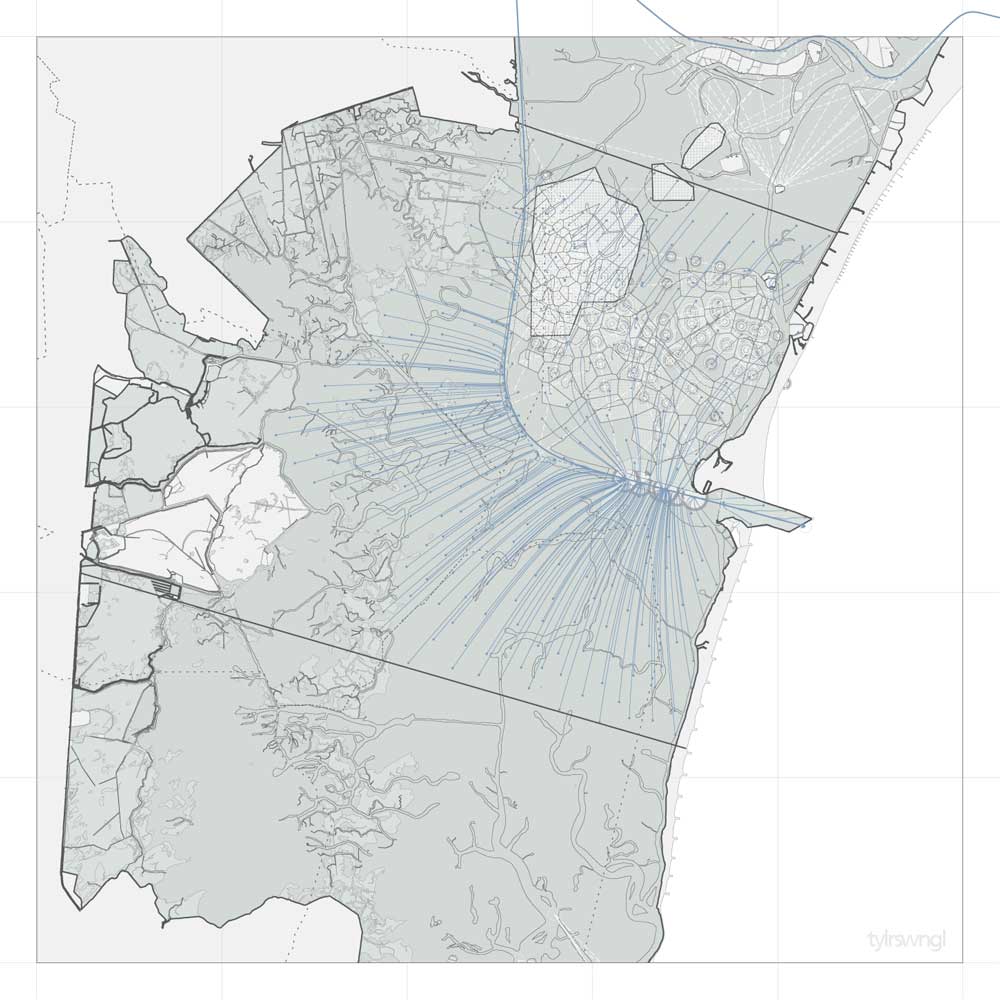

BATHYMETRY OF VENICE LAGOON

The natural setting of the Venetian Lagoon that was once productive, romantic and nostalgic has turned into a threatened environment. As the Venetians responded and adapted to the lagoon in the fifth century, the lagoon has transformed reciprocally to the Venetians, entangled as a co-constructed identity of the lagoon and the inhabitants. Currently, this interconnected relationship is transforming the bathymetry of the lagoon by losing sediment. The loss of sediment is a two-part phenomena induced by the position of inlets into the lagoon and productive economies inside the lagoon. The combination produces low amounts of sediment intake with high amounts of siltation and consequently high amounts of sediment release into the Mediterranean.

The bathymetry of the lagoon is composed by a series of sediment types: sand, silt, and clay. Together, the combination establishes the extent and distribution of potential natural habitats like salt marshes, intertidal marshes, intertidal mudflats, submerged mudflats through bathymetry and topography; the variation of elevations allows for many heterogeneous types of water/land environments.

In a study from Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia and CNR- Istituto di Scienze Marine, the data showed there was an a moderate erosion in the lagoon with differences from 0.10m - 0.50m from 1970 - 2000. The researchers have divided the lagoon into 4 sub-basins, arguing that the different sediment compositions constituted a unique sub-basin within the lagoon.

morphology study; data for sub basins

Molinaroli, Emanuela. et al. ‘Thirty-year changes (1970 to 2000) in bathymetry and sediment texture recorded in the Lagoon of Venice sub-basins, Italy’ Marine Geology 258. 2009.

MOSE PROJECT

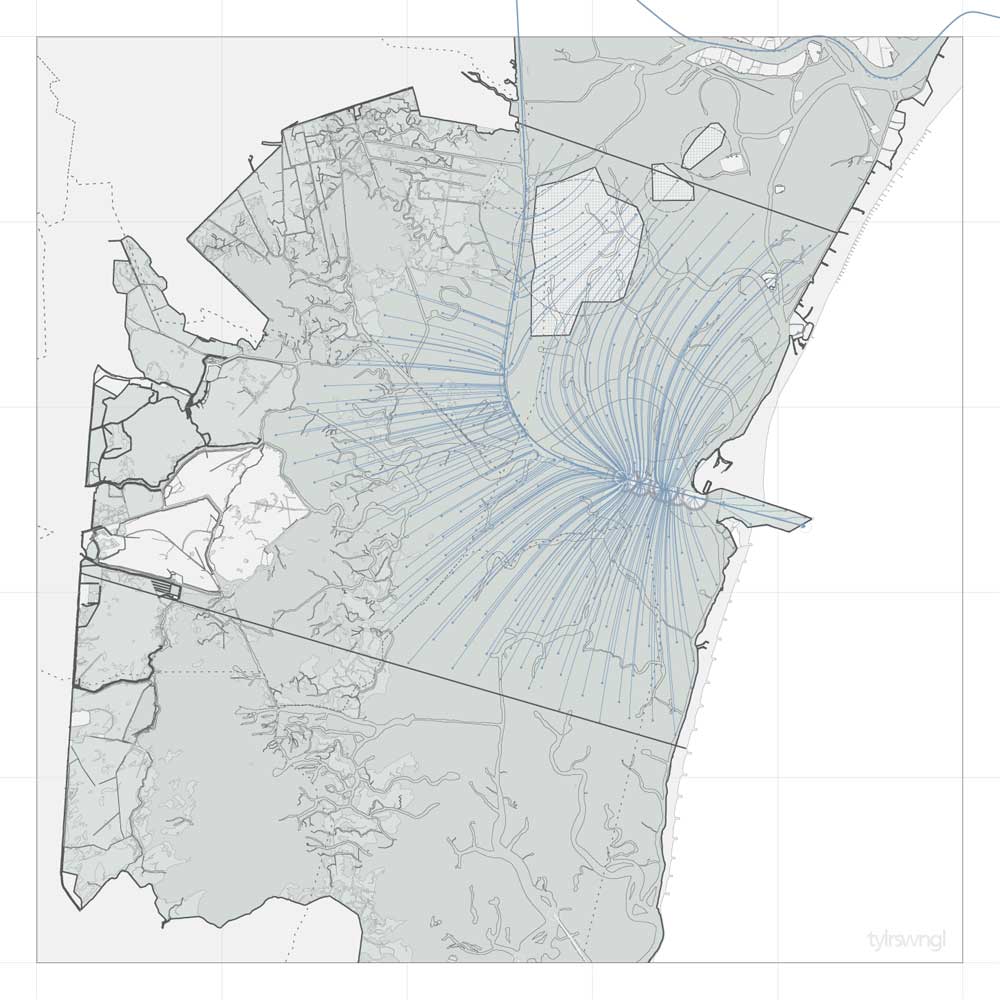

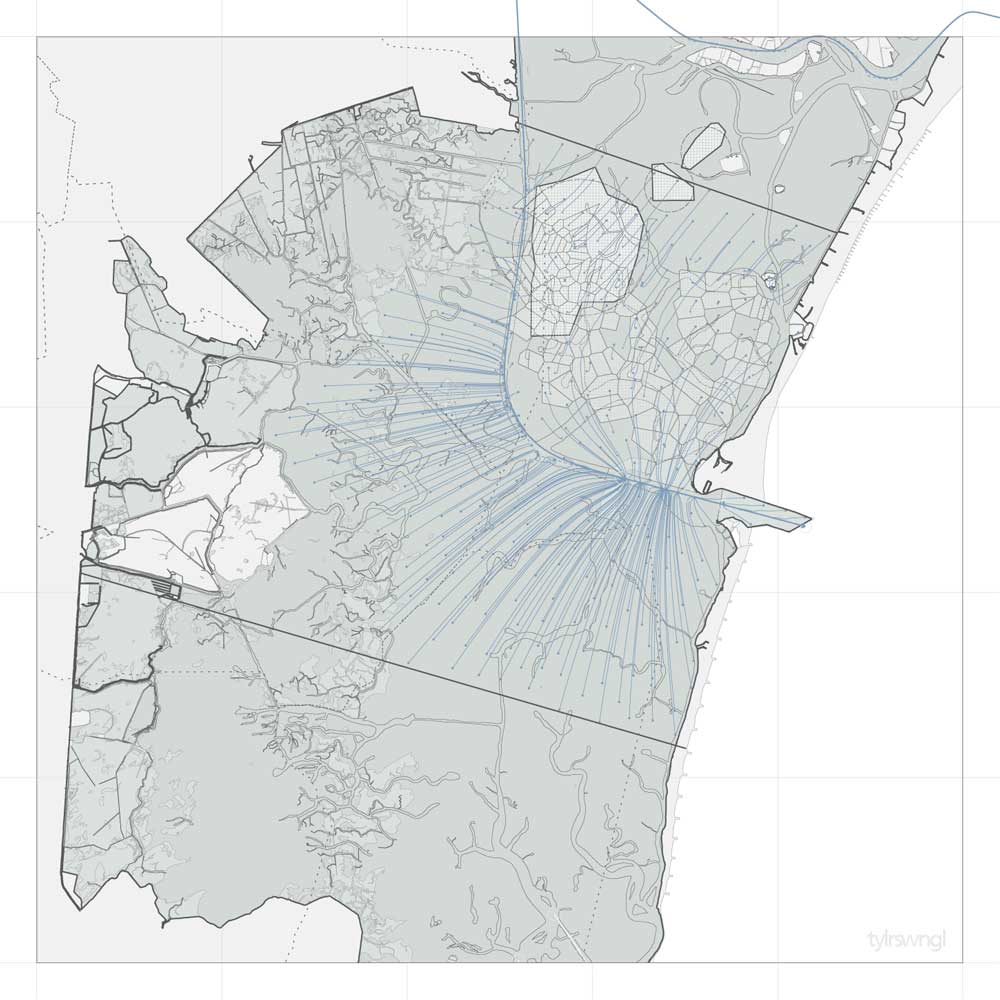

The study showed that basin A [pristine] was still in a quasi-natural condition, with slight clay enrichment and a small degree of deepening [4-5cm] due to sea level rise. The bathymetry and sediment of the sub-basin B [urban] and the sub-basin C [open] were heavily affected by urbanization and industrialization, and effectively created an flat and open lagoon. The sub-basin D [exploited-subsiding] was generally unaffected, but is mostly an artificial environment. The sub-basins expose the specific sedimentation shift, and enables the lagoon to be thought of as four different sub-basins; each requiring a different sediment management solution.

Other state agencies have recorded similar sedimentation depletions results. Similar finding suggest most of the sediment loss is concentrated in the middle part of the lagoon, sub-basin C.

One large, over-all contributing factor to the loss of sediment is the current lagoon inlet configuration, including the MOSE project. ‘Both the tidal prism [the flow exchange capacity between the sea and the lagoon] and the amplitude of the tidal wave propagating into the lagoon have significantly increased.’ It is estimated, with the strong asymmetrical currents in front of the lagoon, a massive amount of sediment from this inlet behavior has created the ‘degradation of many of the morphological structures present in the lagoon.’

On a more local scale, economies inside the lagoon have also effected sediment behavior. Modern economies of the lagoon have typically been focused on material production, both large and small scale. The larger scale production is based in Marghera, and includes refined petroleum products and other basic chemicals for ship building. Other small and medium scale material production in and around the islands of Venice include glass, boats and boat restoration, and fishing. However, material production requires a large area of land, and ‘high location cost make it unrealistic to predict the expansion of the historical center and the coastal part of the city.’

While the current economies sustain from the ease of transportation through the lagoon, easy access to resources from the lagoon, and limited restrictions inside the lagoon, the development of both small and large scale material production has impacted the lagoon in the form of sediment migration.

The following are three types of production, both material and immaterial, identified in terms of their sediment distribution and over-all ecological framework: commercial trade, fishing and clam fishing, and tourism inside the lagoon.

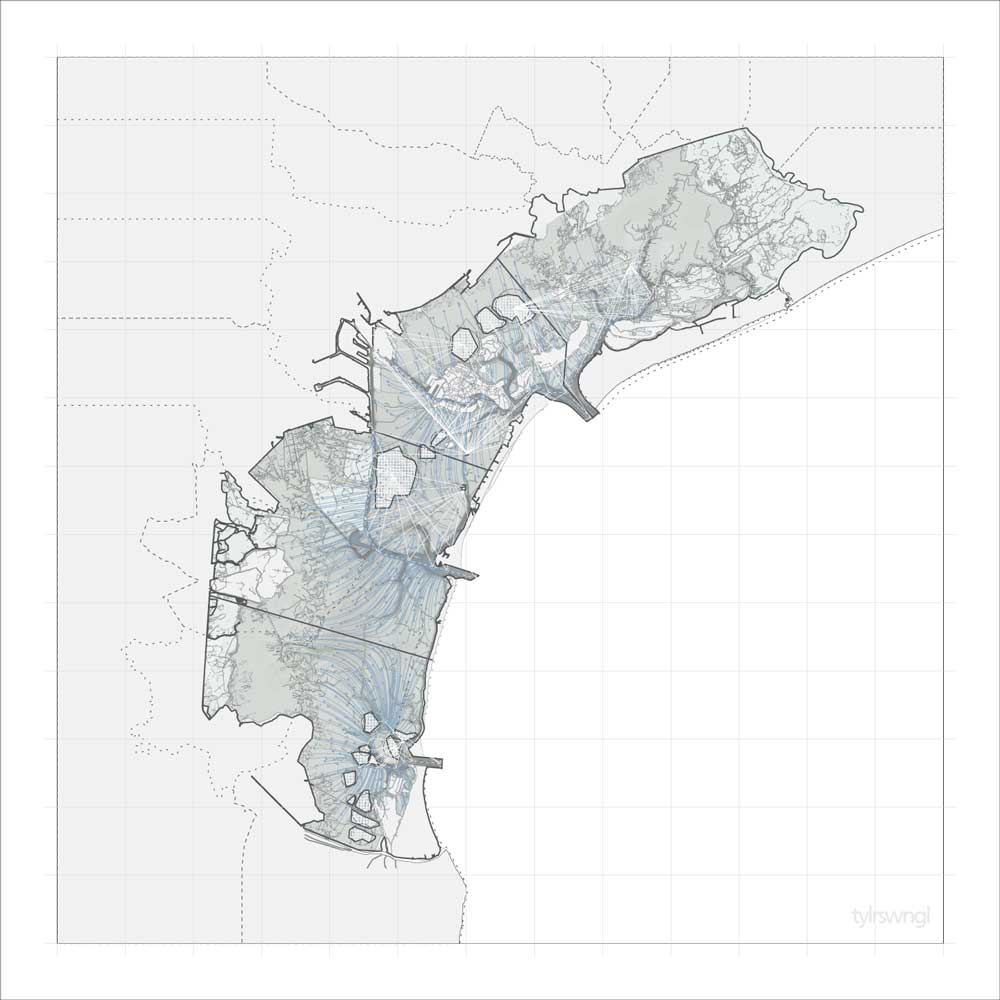

Commercial shipping typically engages with the Port of Maghera, and not the old city of Venice. Traveling through the middle inlet Bocca di Porta di Malamocco, the Maghera-Malamocco Channel cuts directly across the lagoon [inside sub-basin C], and turns along the municipal and sediment-structure boundary of Lago dei Teneri.

The more than 3000 commercial vessels that navigate the channel each year have collectively resuspended 1,200,000 metric tons of sediment. The suspended sediment, due to ‘drawdown’ associated with the many vessels, pulls sediment from the surrounding bathymetry into the shipping channel, creating a two-fold problem. Economically, the process of re-dredging the channel is not sustainable; environmentally, the erosion of sub-basin C bathymetry has created a flat zone that can neither sustain habitats nor can the bathymetry protect itself from further sediment suspension.

Fishing and clam fishing is an economy that relies on common property resources and, although seemingly environmental-friendly, has effects on the sediment distribution of the lagoon. During most of the co-existence between the lagoon and the Venetians, both types of fishing had been limited technically and seasonally. Until recently, ‘the local authority and the fishing cooperatives controlled the fishing activity by fixing prices and amounts of catch, as well as defining and managing specific areas in the lagoon.’

The potential high revenue of clam fishing, along with the invasive species of clams, has spurred an increase of unlimited licenses, as well as technically intensive equipment such as suction dredgers and vibrating rakes. Compared to the abandoned fishing practices of territories and hand rakes, the current production method is disruptive of the sediment, and poses a potential threat to the security of the lagoon’s bathymetry.

Similarly, the fishing industry is also using some sediment-disruptive techniques such as bottom trawling. However, less labor intensive net systems are more common in the lagoon, including gillnets, fixed gillnets, lift nets, and fyke nets. While the nets are less disruptive to the sediment and the habitat it supports, the commercial fishing industry has depleted the fish stock of the lagoon.

While still relying on the ecology of the lagoon as a resource, the maintenance of the habitats and biodiversity should be a key priority for the fishing industry. Studies from both Nunes and Zanatta suggest a behavioral change of fisherman willing to reduce the use of ecologically harmful methods in return for cheaper initial costs like licenses.

Venice’s immaterial economy relies heavily on tourism. This topic is highly debated, and therefore I would like to attempt to only evaluate the type of production in terms of the sediment distribution and habitat disruption.

Unlike the commercial vessels, the cruise ships do not produce a wake traveling through the Lido canal, therefore the immediate impact on sediment is not high. However, a new route for cruise ships proposed to connect the cruise ships with the Maghera-Malamocco Channel. If this were to happen, the frequency of the cruise ships would add to the already large erosion of the bathymetry in sub-basin C. Further, the consumptive demand imposed on the city from the fluctuation of temporary inhabitants reverberates throughout the lagoon, effectively stimulating fishing practices, some sorts of commercial trading, and other economies dependent on the lagoon.

Based on a recent census, the increasing difficulties in maintaining the social base in the historic center of Venice, coupled with the inability to find a means of productive advancement outside of the tourist industry ‘produce a picture of an economic situation which is difficult to sustain.’ As alternatives, Rullani and Micelli suggest a redistribution and reallocation of new immaterial production, anticipating the flexibility and fragmentation of new forms of production. They assume the spatial modularisation will effect both scales of territory and scales of persona, relying on telecommunication and other interactive long-distance networks. Applied at the territorial scale, the potential expansion of the immaterial industry into the lagoon posses a threat of more sedimentation loss at a larger scale.

PROPOSED SHIPPING PORT OUTSIDE OF VENICE LAGOON

VENETIAN FISHERMEN USING A NET SYSTEM

LAGOON FISHING NETS

The proposed new galleys, the sediment-structures, aim to protect and develop both vulnerable ecologies and economies of the lagoon by linking the production of both together.

Each sub-basin of the lagoon is different, and each provides resources for different economies. Therefore, there are different types of sediment-structures, each a manifestation of the appropriate combination between local economy and ecology. The structures need to be adaptive and able to respond to the development of the surrounding ecology and economy by changing distribution and effectiveness.

Above water, the structures provide space, such as platforms, docks, housing, and storage for the economies. Below water, the structures deposit sediment strategically and prevent the over-all loss of sediment in the lagoon.

Critical to the sediment-structure is the ability to distribute sediment in locations that are helpful to operating economies and protective against future sediment suspension. Acting like a snow-fence, the sediment-structure will disrupt the flow of water in highly turbulent areas, allowing for suspended sediment to fall more quickly deposit along the floor of the lagoon. With accumulation, the structure works to rebuild diversity and habitats into the lagoon and sustain a local economy of local production and maintenance.

This process is contextual, and depends on the existing bathymetry of the lagoon floor. The bathymetry can be organized in stages according to the sub-basins bathymetry as:

1] open, urban

2] urban, exploited-subsidized

3] pristine

Each bathymetry is a progression of layering from the previous one, but there is no ideal amount of sediment, only the amount in which the linked economies and ecologies operate simultaneously.